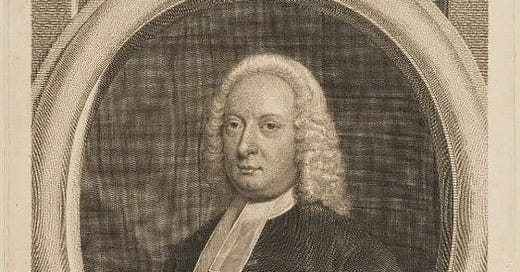

John Gill is an important figure in Baptist history for many reasons. He was the first Baptist to write an exposition on every single verse in the entire Bible. He knew the original languages of Scripture, not from seminary, but largely by teaching himself since his family was too poor to afford higher education. Because of his scholarship, he was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Divinity from the University of Aberdeen.

On top of all this, Gill wrote the first ever Baptist systematic theology, which he titled The Complete Body of Practical and Doctrinal Divinity. After his expositional work, he wrote, “I considered with myself what would be best next to engage in, for the further instruction of the people under my care.”[1] Throughout his whole life, Gill remained faithful to the church he pastored. He wrote with the members in mind.

John Gill’s distinctively Baptistic systematic thinking is an invaluable landmark in our field of history. He is both balanced and insightful. Gill truly believed that faithful systematic theology honors Scripture, whereas today there is a growing sentiment that it distracts or even detracts from it. Perhaps our understanding of systematic theology has changed ever so slightly; we may learn from Gill in this matter.

Historical Context

A serious problem was brewing, and John Gill knew it only too well. He observed, “Systematic Divinity, I am sensible, is now become very unpopular. Formulas and articles of faith, creeds, confessions, catechisms, and summaries of divine truths, are greatly decried in our age.”[2] Why? There are a number of possible reasons. The late eighteenth century marked a major crossway era in the train station of ideas. The wax of the Puritans was waning, and the light of their doctrine was all but expired. Emerging rationalistic enlightenment thinking waged war on experimental Christianity and severely inhibited the proper use of tradition. This, along with the dawn of higher criticism in the 17th century, threw traditional formulations of doctrine under the bus. The residual influence of Spinoza and Hobbes undermined the Reformed interpretation of Scripture by redefining hermeneutics altogether.

Gill primarily desired to write his Divinity to the end of equipping his own church to maneuver through this storm. He wrote with the care of souls in mind. This is evident throughout the whole work because it is eminently doctrinal, brilliantly practical, and useful in bringing the converted reader to his knees to glorify the Lord with prayers of adoration.

Apology for Systems

Given the anti-systematic sentiment, Gill naturally begins his work with a brief apology for the systemization of Scripture. An apology in this context is an explanatory defense. He simply asks, “What art or science soever but has been reduced to a system?” In modern English, he is asking, “What art or science has not been reduced to a system?” By asking such a question, he is placing himself in the shoes of the reader, knowing that the reader will naturally respond in a logical way. This approach is especially helpful because it bypasses the immediate, sometimes emotional reaction to systematic theology that skeptics may have.

Gill lists many arts and sciences which each have their own systems. Medicine, physics, metaphysics, logic, rhetoric, philosophy, and law all have been well ordered for millennia. Hippocrates ordered the elements and practice of medicine so that he could treat his patients well. Aristotle’s Metaphysics had a specific rhyme and reason. He could not simply mention first causes or form and matter; he had to begin with the very first thing: the nature of knowledge. Cicero (if he was the author) had to order Ad Herennium in such a way that rhetoric could be practiced more effectively. He had to organize and assemble his common topics in the most logical way possible. The point is clear: Whether an art or science, a discipline can and ought to be systematized.

What exactly does Gill mean by a system, though? He defines it as, “an assemblage or composition of the several doctrines or parts of a science.” If a discipline is truly a science, then it has parts. Those parts, in order to be understood well, should be arranged in a natural order. The forest is grand taken as a whole. But if one desires to know what the forest is, he must walk through it. When he sees the trees, one would hope that he can distinguish them from the shrubs and the shrooms. If he is a good student of the forest, he will go further. He will take samples home; he will draw the different plants; he will test the soil; he will visit during the different seasons. Such a man collects all the parts, and then he returns home and assembles them into a Tree-ology, entitling it “A Treatise on the Nature of Vegetable Life in the Forest, from the Root to the Leaf, Commonly Referred to as Botany.”

The next question Gill puts to the reader makes the whole argument come alive: “Why should divinity, the most noble science, be without a system?” Like the forest, the Bible is made up of many different parts. There are histories, prophecies, allegories, visions, dissertations, and letters. But unlike a common forest, the Bible is more like the redwoods, or cedars of Lebanon. It is an ancient forest which God Himself planted. Such a forest surely would not be offended at being the subject of a systematic study. Rather it would rejoice. God delights in His little ones when they study the great things in His Word and seek to sort them all out. Gill’s point is, “To gather them together, and dispose of them in a regular, orderly method, surely cannot be disagreeable.”

In order that he might assure the reader that this is true, he offers three reasons to show the usefulness of systematizing Scripture. First, systems of Scripture provide the Christian with a more perspicuous understanding of Scripture. Gill is not denying that the Scriptures are sufficient to bring a sinner to a knowledge of the gospel and the reality of conversion by the Holy Spirit. But, as the 2LBC states, “All things in Scripture are not alike plain in themselves, nor alike clear unto all” (1.7). Systematizing Scripture, according to Gill, can make these things more “perspicuous.” In using that word, Gill is not undermining the doctrine of the perspicuity of Scripture; he is using it to demonstrate that systematics can help explain difficult passages. Webster’s 1828 dictionary defines “perspicuous” as, “Clear to the understanding; that may be clearly understood; not obscure or ambiguous.”[3]

Second, systems of Scripture help the Christian retain the key doctrines of Scripture in his memory. This point is quite straight forward. Those who are equipped with a well ordered system of Scripture can turn it to great advantage. Each head of theology, each part of doctrine serves as a reference point which can remind the Christian where it is contained in Scripture. This kind of recall also helps him quickly distinguish good and bad theology.

Third, systems of Scripture show the Christian the connection and harmony of all Scripture, helping him put the analogy of Scripture into practice. On this point, Gill is fundamentally agreeing with the 2LBC 1.9:

The infallible rule of interpretation of Scripture is the Scripture itself; and therefore when there is a question about the true and full sense of any Scripture (which is not manifold, but one), it must be searched by other places that speak more clearly.

Systematizing the Scriptures is one way of comparing Scripture with Scripture. Doing this can help struggling Christians understand harder parts of Scripture.

At this point, it is apparent that the way Gill talks about systematics is slightly broader than modern systematic theology. Modern systematic theologies tend to be quite lengthy. They usually use the same heads of theology (though they still debate about the proper order), such as theology proper (God), anthropology (man), hamartiology (sin), Christology (Christ and redemption), etc. All this falls under Gill’s definition of systematics, but Gill also leaves ample room for short creeds, catechisms, and confessions. He even argues that certain parts of Scripture are in themselves systematic!

Systems in Church History

Systems of theology are not a modern invention. Gill identifies the early church creeds of the first four centuries as a form of systemizing Scripture. Here it is good to point out that the Particular Baptists, considering themselves in many ways heirs of the Reformation, did indeed hold to and confess the early church creeds.

To this point, however, Gill adds a caveat. He in no way downplays the creeds, but he writes that the bodies of divinity and confessions which came out of the Reformation were “better digested, and drawn up with greater accuracy and consistence.”[4] Gill believed that systematic theology has matured throughout the history of the church, though because of the error of Popery it also regressed at times (see Part II). The history of systematic theology is like gouda cheese; the more it is aged, the more complex and robust it becomes. But in some cases, even good gouda can become sour and overly moldy.

Gill identifies three particular uses of studying systematic theologies like the Nicene Creed, Apostles’ Creed, Athanasian Creed, Canons of Dort, Westminster Confession of Faith, and the First and Second London Baptist Confessions of Faith. First, these lead men into a knowledge of true evangelical doctrine. Many Christians can attest that after living many years following Christ, they stumbled upon such systems and came to a deeper and more Scriptural understanding of doctrine through them. Second, systems confirm those who are farther along in their understanding of doctrine. The mature Christian may use them as reference points and helpful resources to return to. Third, systems demonstrate the agreement and harmony of sound theologians throughout church history. These historical creeds all attest to, “one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all, who is over all and through all and in all” (Ephesians 4:5, 6 ESV).

Systems in Scripture

John Gill fascinatingly argues that Scripture exhibits characteristics of systems within itself. When considering the ten commandments, Gill marvels,

What a compendium or body of laws is the decalogue or ten commandments, drawn up and calculated more especially for the use of the Jews, and suited to their circumstances! A body of laws not to be equaled by the wisest legislators of Greece and Rome, Minos, Lycurgus, Zaleucus, and Numa; nor by the laws of the twelve Roman tables, for order and regularity, for clearness and perspicuity, for comprehensiveness and brevity.

Within the decalogue Gill sees all the elements of a well-ordered system, one which surpasses all the laws of classical antiquity. Gill also points to the Lord’s prayer as being a system, consisting of petitions which are “the most full, proper, and pertinent, and in the most order.” It is no wonder that both the Orthodox Catechism by Hercule Collins (the Baptist version of the Heidelberg Catechism) and the Baptist Catechism (the Baptist version of the Westminster Shorter Catechism) both include a systematic treatment on the Lord’s prayer.

He offers Hebrews 6:1, 2 as another example. It consists of six articles, which are repentance, faith, baptism, laying on of hands, resurrection, and the eternal judgement. There are indeed many similar passages which Gill does not mention. Baptists would do well to search them out and admire the order and beauty of God’s perfect word.

A Critique of No Creed but the Bible

Gill mentions that some in his day argued that the church’s creeds should only “be expressed in the bare words of sacred Scriptures.” This point of view has been called “No creed but the Bible.” Some also call it “Biblicism.” Biblicism, according to Gill, has many implications which can easily lead to error. It should be noted, however, that sometimes people claim to be Biblicists, and what they really mean is that they put the Bible first above all other things, and that only the Bible is necessary for salvation. This instinct is good. Rest assured that Gill would heartily agree. The 2LBC, itself a system, opens with this powerful statement: “The Holy Scripture is the only sufficient, certain, and infallible rule of all saving knowledge, faith, and obedience” (1.1). Gill is instead arguing against people who think that systems are unbiblical and even sinful.

The first implication is that Biblicism destroys exposition and interpretation of Scripture: “For without words different from, though agreeable to the sacred Scriptures, we can never express our sense of them.”[5] If I am in class and my professor asks me to explain a Herbert poem, and if I respond by reading the poem back to him, have I truly explained it? Of course not! In the same way, systematic theology is, at its root, simply an explanation of Scripture. It is not claiming to be Scripture.

The second point Gill makes is that Biblicism practically renders preaching the word useless. If one is not allowed to write the doctrines of Scripture using explanatory words, then speaking the same thing would be just as bad. Third, Biblicism stifles religious conversation about divine things for the same reason. Fourth, Biblicism makes it unlawful even to conceive anything concerning Scripture except for Scripture itself. To even think systematic-like thoughts would be a grievous thing. If a Biblicist thought the word “Trinity,” which nowhere appears in the Bible, he would be very inconsistent indeed. The fifth implication is that there can be no distinction made between the convictions of one man and another. If Arius and Athanasius were only allowed to use the literal words of Scripture apart from their creeds, there would be no noticeable distinction between them! They appealed to the same passages. The difference was their interpretation of them.

Next Up

In Part I we considered John Gill’s understanding of systems. In Part II we will see how he ties theology into systems. You will be in for quite the surprise, because his ideas of systematic theology become even more distinct from modern notions, and I trust they will be useful.

Particular Applications

1. John Gill did not begin to write his systematic theology until after he completed his exposition of all the Scriptures. Have you read the Bible in all its fullness? It is essential that you read the entirety of the Scriptures. Systematic theology has its place, but it must be done on top of, not in place of, Scripture.

2. John Gill wrote his systematic theology with the further instruction of his local church in mind. When you read or even write systematic theology, are you doing so with the intent of building up your local church? You ought to be encouraging the saints with the doctrines you read about.

3. John Gill marveled at the order and simplicity of the law of God. Have you ever stopped to think about parts of Scripture as systems? It may prove beneficial. Try reading the Lord’s prayer in Matthew 6 and looking at the main parts it contains, and see if you can label each part with an explanatory heading. Compare your thoughts to the Baptist Catechism, questions 107-114 (https://baptistcatechism.org/). Leave your findings in the comments if you like!

[1] John Gill, Complete Body of Practical and Doctrinal Divinity: Being a System of Evangelical Truths Deduced from the Sacred Scriptures, Abridged by William Staughton, D. D. (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves, 1810), ix.

[2] Ibid., ix.

[3] “Perspicuous,” Websters’ Dictionary 1828 (Accessed March 24, 2025), https://webstersdictionary1828.com/Dictionary/Perspicuous.

[4] Gill, x.

[5] Ibid., xi.